Introduction to Redlining: What is “Redlining” and how has it impacted Jacksonville?

Introduction

For more than 20 years, LISC Jacksonville has been committed to transforming Jacksonville’s most challenged and under-resourced urban core neighborhoods into healthier, more sustainable communities. Our work has always centered around people, equity, and facilitating systemic change in these communities to enable their residents to thrive.

An essential component to this work is understanding how these communities have evolved to where they are today and how past policies have impacted this evolution in order to identify, recommend, and implement potential solutions.

Many in our community, and across the country for that matter, have either ignored or been unaware of a Great Depression-era practice called “redlining” for years. In short, it’s a part of history that has never really been taught or discussed, particularly among those who do have knowledge of it. However, that is changing in cities across the U.S.

Locally, LISC Jacksonville has taken the lead on evaluating redlining’s generational impacts on our city’s most under-resourced and under-invested neighborhoods. Using a variety of resources, including Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) ArcGIS data, US Census Data, Duval County property data and historic maps, we have been conducting a deep-dive exploration of redlining. We have also assembled several local and regional partners, including the University of Florida, to support our efforts. We look forward to sharing this information with the public.

In a series of articles in the coming months, we will explore the topic of redlining and what we have learned from our work in this area and provide recommendations for how our city can acknowledge and reverse decades of adverse actions and public policies.

What is Redlining?

First, we must explain the practice of redlining and how it came to be.

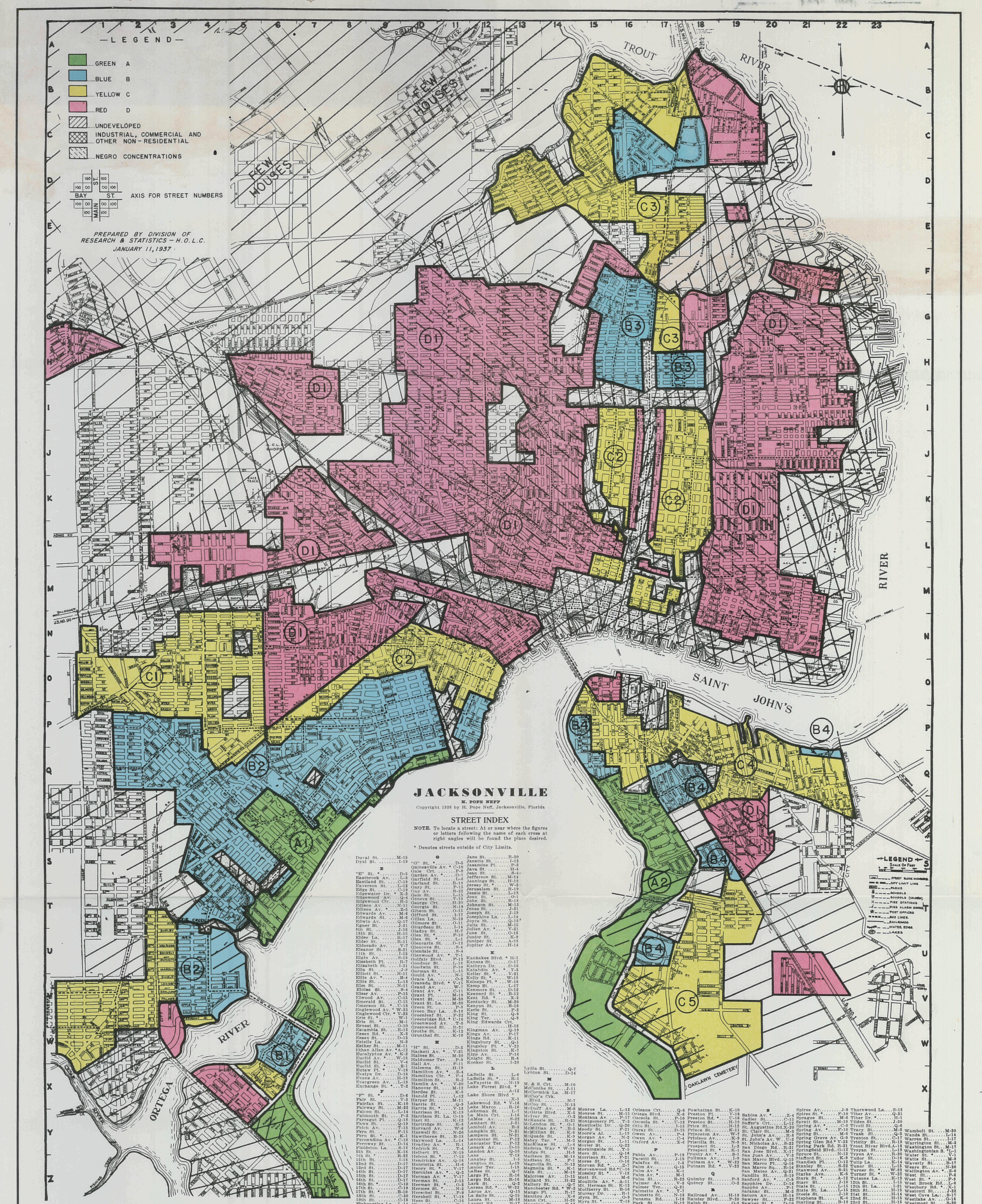

During the Great Depression, the U.S. Government created the Home Ownership Loan Corporation (HOLC) to help Americans purchase homes and help stimulate economic recovery. Neighborhoods in cities across the country were segmented and mapped based on a perceived risk in lending, which guided lenders in making decisions about where and to whom to provide mortgages. This segmentation and mapping was the birth of redlining.

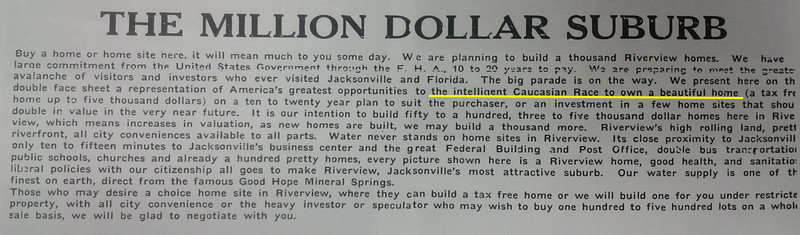

These “perceived risks” in lending were based on both financial and racial considerations, as evidenced by explicitly racialized language used in official documents at the time. Segmentation via “Residential Security Maps” identified neighborhoods that were considered low-risk (labeled A & B) and moderate-risk (labeled C) where they would make loans, and neighborhoods deemed too high-risk (labeled D) where they would not lend at all.

As a result, predominantly BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities were placed in the red, or too high-risk, zone, nearly eliminating residents’ access to mortgages, refinancing options, or small home improvement loans – hence how the term “redlined neighborhood” came to be. This was deemed justifiable by the Federal Housing Administration at the time, which alleged that wherever African Americans purchased homes, property values were guaranteed to fall.

The main point is that race played a key role in determining where lenders would lend.

Redlining in Jacksonville

In Jacksonville, redlining was implemented in 1937. By designating BIPOC communities as too high-risk or “Hazardous,” the homes in these communities – such as northwest Jacksonville, Historic Eastside, and many others – had almost no market value, effectively cutting these neighborhoods off from any potential investment. Mortgages weren’t available to BIPOC homeowners, and as a result, homeowners could only hope to sell their home to those who paid in cash (significantly reducing value) and it rendered them ineligible for home repair loans, leading to physical deterioration of their properties. As such, property values in neighborhoods such as Durkeeville plummeted while neighborhoods such as Riverside enjoyed access to fiscal tools that provided economic certainty.

While Jacksonville’s first zoning map was completed in 1930, before redlining, it was eerily similar to the redline maps that were to come. The zoning map designated Restricted and Unrestricted/Industrial areas that prescribed allowable land uses. Almost all BIPOC communities were placed in the Unrestricted/Industrial zone, allowing nearly any type of development. This resulted in incinerators, factories, and other undesirable development being built right next to African American’s homes, further depressing property values and exposing residents to unhealthy living conditions that continue to this day.

When redlining took effect seven years later, the practice further legitimized and perpetuated the existing racial segregation in housing by reenforcing then-legal tools such as racially restrictive housing covenants in numerous neighborhoods, such as Riverside. These covenants, which were attached to property deeds, directly prohibited property from being sold or leased to African Americans. So, BIPOC residents were not only unable to improve their existing properties; they were also unable to relocate to more desirable parts of town – even if they could afford to do so. This practice continued for another 30 years, during a time when Jim Crow laws were also prolonging racial segregation across nearly all aspects of life.

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed racial segregation in housing, BIPOC communities were historically deprived of the ability to generate wealth through homeownership due to the practice of redlining, while white communities prospered. The result: significant, racialized gaps in financial prosperity and other areas that exist to this day.

Today, Jacksonville’s most challenged and under-resourced communities are precisely those that were deemed un-lendable by redline maps nearly 100 years ago.

This is precisely why LISC Jacksonville has undertaken this work. We have the capacity, tools, and resources to examine the issue of redlining and the impacts it created that exist to this day. At its core, our redline deep-dive initiative is about recognizing the role that both public and private policy played in perpetuating race-based inequality. It is also about the need to use policy to right these wrongs and dramatically improve the historical gaps in resources that have occurred in the neighborhoods we care about.

This is precisely why LISC Jacksonville has undertaken this work. We have the capacity, tools, and resources to examine the issue of redlining and the impacts it created that exist to this day. At its core, our redline deep-dive initiative is about recognizing the role that both public and private policy played in perpetuating race-based inequality. It is also about the need to use policy to right these wrongs and dramatically improve the historical gaps in resources that have occurred in the neighborhoods we care about.

Next month, we will further evaluate the demographics involved with redlining, including racial profiles, unemployment, income, and poverty.

To learn more about the communities in which LISC Jacksonville operates, click here.