How South LA Is Increasing Economic Opportunity Through Inclusive, Place-Based Solutions

This post was originally published on brookings.edu

This winter, The New York Times released an in-depth portrayal of homelessness in Los Angeles. Rather than pointing to housing shortages or escalating costs of living as the primary culprits, the authors offered a more comprehensive diagnosis: Interconnected legacies of racism, disinvestment, and displacement—all rooted in place—are to blame.

While most of Los Angeles (and the state of California) is feeling the ramifications of housing insecurity and economic inequality, the Times article showed how a constellation of factors have converged to cluster homelessness and poverty in one particular part of the city: South L.A. These factors—including redlining, manufacturing decline, and demographic shifts over time—have tilted the balance of opportunity so that those raised in South L.A. are disproportionately restricted from economic and social mobility compared to the rest of the city.

To tackle such interconnected, place-based challenges, the city must adopt interconnected, place-based solutions. So, LISC LA and an array of local community and economic development organizations are piloting a new approach for economic inclusion – one that starts with South L.A., but is replicable in historically disinvested communities throughout the country. This approach is based on the belief that entire cities can reduce inequality by coordinating workforce, small business, real estate, and community-based development efforts in a small set of historically disinvested districts.

Different groups, shared goals

To further this place-based and people-centered approach, LISC’s Economic Development Initiative—in partnership with local LISC offices, advocates, community organizations, planning consultants, public officials, neighborhood, city, and regional economic development stakeholders, and national partners such as Brookings’s Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking and Mass Economics—is testing a Community-Based Economic Inclusion Demonstration in three high-poverty communities in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Indianapolis.

The demonstration, which is about six months in, broadens the conventional understanding of economic development and who takes part in conversations about solutions. There is often consensus that we must address homelessness, invest in historically disinvested neighborhoods without displacing long-term residents, and support Black businesses and entrepreneurs. But the community organizations and economic development stakeholders working to achieve these goals often operate in siloes, sitting at different tables and missing opportunities to capture collective momentum over shared solutions.

Our approach seeks to change this by aligning the rich cultural and local knowledge of neighborhood-based organizations with citywide and regional entities in the co-creation of shared Economic Inclusion Agendas. These agendas will leverage the financial resources, technical expertise, and cultural knowledge of the economic, workforce, and community development ecosystems to advance a shared equity vision for promoting opportunity in high-poverty places.

Each city’s path to this goal is a bit different depending on local realities, but they share a common aspiration: to promote a holistic approach to economic development that recognizes the multiplicity of challenges facing high-poverty communities, and tangibly increases economic opportunity for those living in them.

Building on a community’s strengths

Like many processes, ours starts with data. But rather than using data to diagnose places’ challenges, we are uncovering their assets.

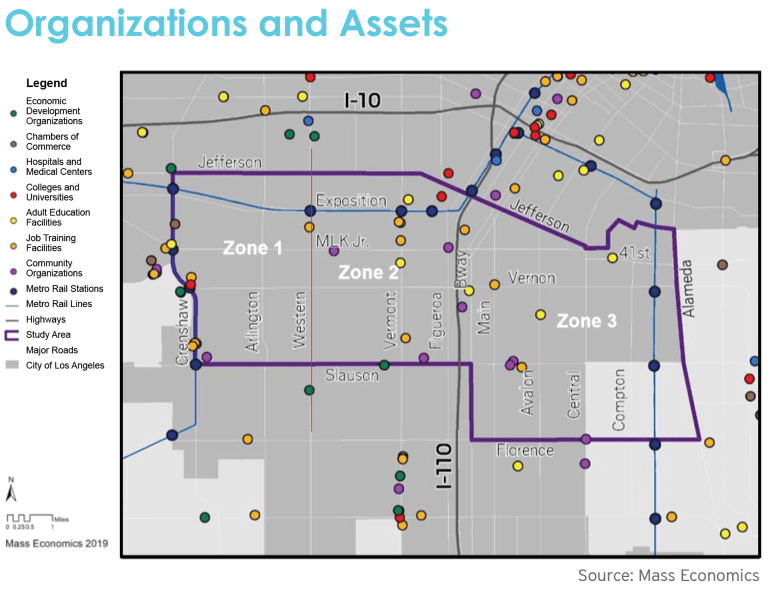

Let’s take South L.A. We know the area faces deeply rooted place-based challenges. But we also know it is home to unique economic and cultural strengths. Using market analyses conducted by Mass Economics, we divided subportions of South L.A. into three zones based on assets.

Zone 1 includes the Crenshaw Corridor—referred to as the Main Street of Black Los Angeles and home to projects such as Destination Crenshaw and a new transit project that will connect to the airport. Zone 2 includes anchors such as the University of Southern California and Exposition Park, which will be a source for jobs and training opportunities for residents. Zone 3 encompasses the Goodyear Tract, an industrial district with a diverse collection of jobs.

We cross-checked these zones’ data with data on emerging regional industry clusters already supported by citywide economic development stakeholders. This ensures that our efforts target and prioritize industry clusters with the potential to create good-quality jobs for residents. Using these data to identify assets and opportunities in parts of South L.A., we are basing our agenda in the community’s strengths, rather than challenges.

That doesn’t mean we ignore the challenges. After identifying zones in which to implement our agenda, we used data to understand the characteristics of economically disadvantaged populations in the area, the challenges they face in health, food, and environmental justice, and their employment patterns and consumer flows.

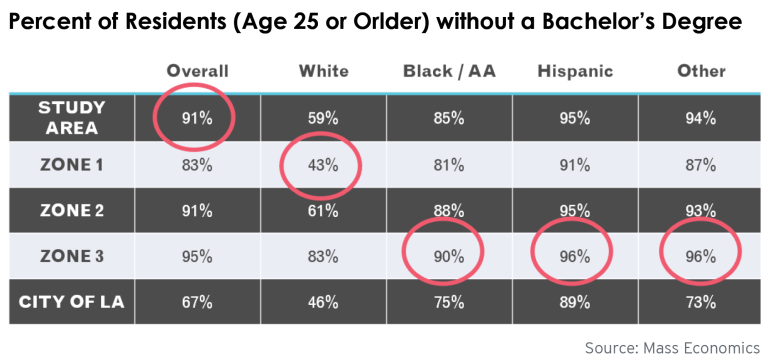

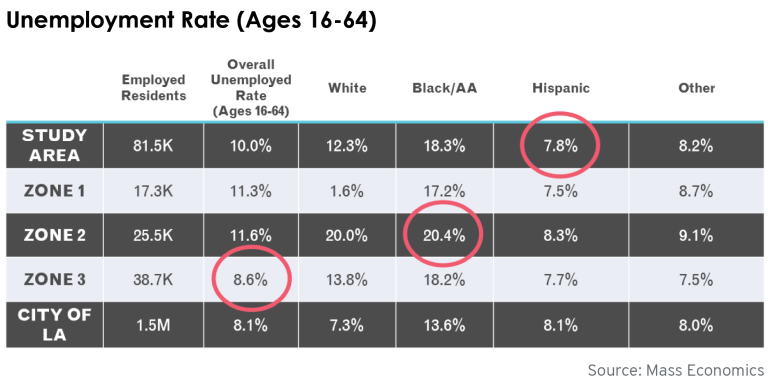

What we found wasn’t necessarily a surprise. Residents in these areas of South L.A. are disproportionately people of color, have lower educational attainment, experience high levels of poverty, and are largely restricted from the good and accessible jobs available in the area.

They face higher than average unemployment rates—particularly Black residents—and if they are employed, they are often commuting over 50 miles to work low-paying jobs.

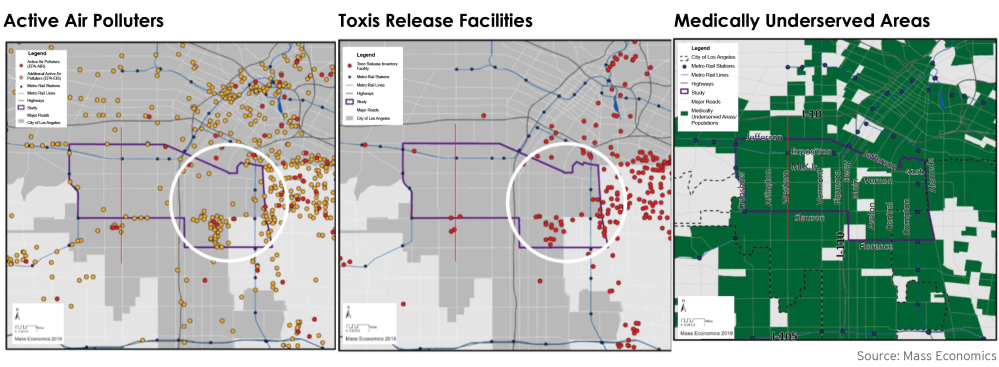

They live in an area disproportionately concentrated with active air polluters and toxic release facilities, yet remain medically underserved.

At the end of the day, the data didn’t necessarily tell our local stakeholders anything they didn’t already know from lived experience. But instead of another research study on South L.A.’s challenges, we are using that data to identify how South L.A. can benefit most from resources, bring economic mobility to those who need it, and make a dent in a long legacy of place-based discrimination.

After distilling the data, we are conducting interviews with local planning consultant Estolano Advisors to add rich history and knowledge that quantitative measures can’t capture. This will be codified into a public Economic Inclusion Agenda, to be released in Spring 2020 and implemented over a three-year period. LISC LA will play a convening role throughout the implementation period, keeping partners and community members focused on our collective vision for place-based equity.

A collective voice, and the investment to back it up

When we embarked on this process, our hope was to harness even a fraction of the collective wisdom South Angelenos hold, and to translate that wisdom into community-led change. We are beginning to see this take hold: Community groups, stakeholders, and public and private sector leaders are transcending traditional understandings of economic development to promote place-based and people-centered growth. Together, we are creating a blueprint to bring opportunity and locally empowered prosperity to South L.A.

But seeing this through will require long-term investment. The area’s challenges are rooted in a deep history of discrimination that transcends geographic boundaries and distinct policy decisions. To correct it, we will need the ongoing support of not just the South L.A. community, but public and private sector leaders within and outside neighborhood lines. Only once a diverse collection of stakeholders values the unique strengths of South L.A. and are willing to consistently invest in community-directed strategies can we co-implement an Economic Inclusion Agenda that benefits residents directly.

If we want to address the nation’s homelessness crisis, the job discrimination that accompanies felony records, the poor street conditions that disconnect residents from accessing opportunity, or the racial wealth gap that displaces entire communities, we must advance holistic, integrated strategies that lead to connected, vibrant, and inclusive places.