In honor of Women's History Month, we are profiling some of the extraordinary women who conceived and shaped our current community development, social justice and anti-racist movements. Their stories may not be widely known, but their intelligence, insight, passion and unrelenting efforts blazed the path we walk today.

“Everyone in San Antonio knows about little Emma Tenayuca, a slim, vivacious labor organizer with black eyes and a Red philosophy.”

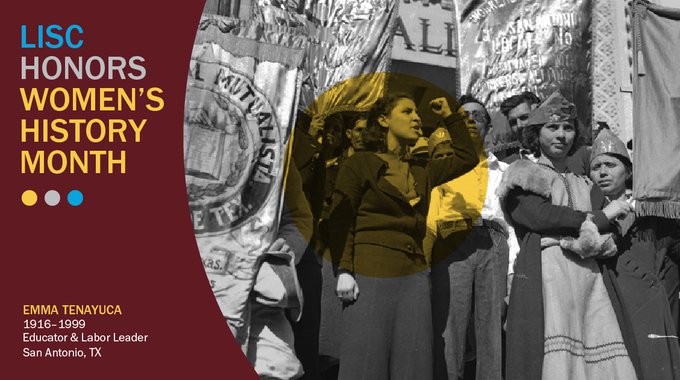

That’s how a February 1938 issue of Time magazine, with the casual sexism of its time, described a Mexican American woman leading thousands of workers in the biggest strike in San Antonio history. The pecan shellers of that city had walked off the job in January and called for her leadership, chanting “Emma, Emma.”

They wanted what many workers strive after even today—a living wage. Pulling the meat from pecan shells was hard, temporary work, often part of a circuit of migratory Mexican American farm labor that would take workers as far away as Colorado. Management had just cut the pecan pickers’ pay from seven cents to six cents per pound of cleaned pecan halves. “Pin money” was the euphemism of the day for women’s wages. Wages that left families literally starving.

Emma Tenayuca was only 21 years old during the three-month strike that made her famous. But she was already powerful and deeply committed to improving the wellbeing of her community and that of all low-wage workers. Her family history in South Texas stretched back generations. The eldest of 11 children, Tenayuca was raised by her maternal grandparents in San Antonio’s West Side barrio. They voted, and closely followed local politics as well as events of the years-long Mexican Revolution across the border. When her grandfather, a carpenter, came home from work and opened his paper, she’d sit opposite him and read the other side. On Sundays, he would take her to the city’s Plaza del Zacate (now Milam Park), where she watched contractors hire families for backbreaking work in beet and cotton fields, and listened to passionate speeches on politics, labor, and religion.

By the time she was 20, Tenayuca, an excellent student, had already read Marx and Tolstoy. She knew the methods of the Industrial Workers of the World or “Wobblies,” an international labor union, and was well acquainted with the anarchist Magonistas of Mexico and their newspaper Regeneración. In fact, Tenayuca sat on the executive committee of the Workers Alliance of America, which organized and advocated for the unemployed and underemployed, and was general secretary of ten Alliance chapters in San Antonio representing some 10,000 workers. She was a veteran of picket lines, demonstrations, and letter-writing campaigns aimed at, among other things, getting equal treatment for Mexican Americans in the New Deal’s subsidized jobs and relief programs.

She knew the suffering of the Great Depression, too—not just from the hunger and poverty of jobless workers she saw hunkered down in shacks without running water, but also from her grandfather, who, nearing 70, confided to her that he’d lost his life savings in the banking crisis of 1933. Emma Tenayuca was, in fact a “Red”—a member of the Communist Party USA, whose vision of power for working people, like her own, emphatically included women and people of all races. When she was a child, her grandparents modeled respect for their Black neighbors, and abhorrence of the local KKK.

But in the 1930s, with the Left divided by doctrinal battles and American suspicion toward Communists hardening to hatred, Tenayuca’s affiliation with the party led to deep personal suffering. Besides mass arrests and tear gas, San Antonio’s police chief and mayor used red-baiting to put down the pecan pickers. Through an intervention by the governor, they eventually won a pay increase, but the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), the umbrella union with which Tenayuca’s Workers Alliance was affiliated, removed Tenayuca as strike leader. She continued to work on picket lines and write circulars for the movement.

But things got harder still. In 1939, when Tenayuca and her husband, a former candidate for Texas governor on the Communist Party line, held a political gathering in San Antonio’s Municipal Auditorium, a violent mob of five thousand, including Klansmen, stormed the building, injuring police and breaking through their barricades. Under order from a new progressive mayor, the police secreted Tenayuca and her companions out through an underground tunnel.

By 1940, Tenayuca was unable to get work and feared for her safety. She fled her lifelong home for Houston, then, in 1946, moved to San Francisco. During this period, she divorced and left the Communist Party. She earned a bachelor’s degree from San Francisco State University and became a teacher.

In 1968, after nearly 30 years away, Tenayuca came home again to San Antonio, where she taught until retiring in 1982. “To my surprise,” she later told an interviewer, “I return and I find myself some sort of heroine.” As the years wore on, younger generations recognized Tenayuca’s prescience and courage as defender of the poor, labor activist, feminist, champion of racial equity—“speaking out,” as the poet Carmen Tafolla wrote in a composition for Tenayuca’s funeral in 1999, “at a time when neither Mexicans nor women were expected to speak out at all.”

A decade before she died, Tenayuca was videotaped in an oral history interview for the University of Texas. Her dark eyes sparkle behind large glasses. She gives the journalist interviewer a slightly hard time, resisting his urgings to talk about her feelings and motivations. Then he asks about the pecan shellers strike: “On a philosophical level, what was it you wanted to accomplish, was it dignity for the people?”

Her exasperation bubbles over. “Food!” she exclaims. “Food! There was a great need for food, there was a great need for jobs. And I suggest that you get two books out of the library, hmm? They’re large books, very very simple. One is called The Great Depression, by a fellow named Katz. The other is Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”