LISC's newest research report offers powerful evidence that racism, financial exclusion and disinvestment have paved the way for speculators to reap huge profits in neighborhoods of color. But there’s good news, too: Buildings with affordability subsidies are better maintained and remain protected from speculation.

For most people, a home is a place of security for themselves and loved ones. For homeowners, it’s also a source of longer-term, intergenerational wealth.

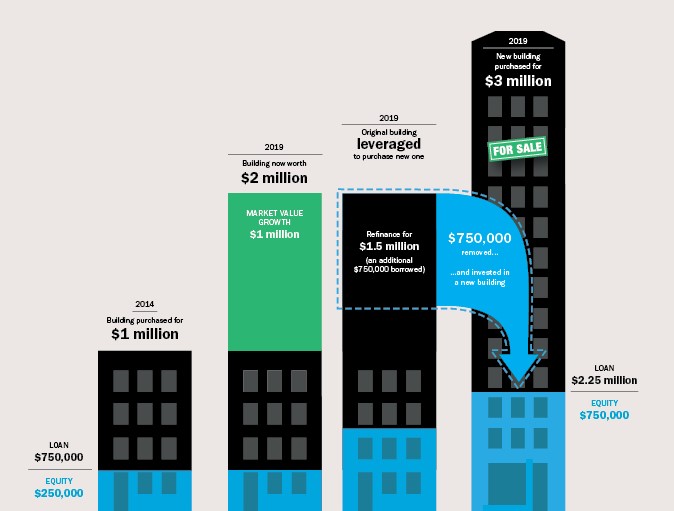

For large corporate landlords and private equity firms, housing is an asset class to be bought and re-sold for higher and higher values. Housing portfolios are also sources of relatively cheap capital – that is, they’re used as collateral for inexpensive debt that companies and individuals can invest elsewhere, achieving much higher rates of return than they pay in mortgage interest, as shown in this infographic below.

PULLING OUT EQUITY: AN ILLUSTRATION

Between 2014 and 2019, the appraised value of a building rises from $1 million to $2 million. Based on this appraisal, the landlord, who originally purchased the building with the help of a $750,000 loan, refinances for $1.5 million. Rather than reinvesting the additional $750,000 in repairs and maintenance to the original building, the landlord uses it to purchase an additional, $3 million property.

When an investor treats housing as an asset, and assumes some risk for the chance of higher returns, it’s called speculation. Some have defended speculation in the housing market as a way to spark investment in long-neglected rental properties where people of color and people making lower wages often live.

This report, Gambling with Homes, or Investing in Communities empirically examines that claim, drawing on a unique database that connects information about apartment building finances, housing maintenance quality, and eviction warrants for over 70,000 rental properties throughout New York City.

Our research, a collaboration between LISC and the University Neighborhood Housing Program, shows that racism, financial exclusion, and disinvestment have indeed created opportunities for speculators to profit. We find that investors and large landlords saw the greatest returns in lower-income, Black and Latinx neighborhoods experiencing some signs of gentrification.

Considering that this is New York City, it is especially remarkable that returns were highest not in Manhattan’s richest neighborhoods but in places where residents have been excluded from wealth – for example, in parts of the Bronx, the borough where about 40% of children live in poverty. The neighborhoods most affected by speculation also tend to be the places hit hardest by COVID-19.

In other words, neighborhoods of color that are still harmed by redlining and other policies and practices of financial exclusion are now sites for extracting wealth, by investors who presumably live elsewhere.

Our research also shows that these profits come at a terrible cost to tenants. Buildings which rose the most in price or which took at the greatest additional debt successfully evicted their tenants at 1.5 times the rate of similar buildings in comparable neighborhoods. And, contrary to the claim that increased lending to multifamily buildings benefits tenants and communities, buildings that experienced speculation had up to 2.7 times the maintenance violations of properties that did not.

Put another way: the greatest wealth increases are achieved at the expense of BIPOC tenants, who are unquestionably harmed by this profiteering.

At this moment, it is especially critical to understand the market forces and actors that help drive the eviction crisis. After the US Supreme Court held the CDC’s eviction moratorium to be illegal, eviction filings increased by 20 percent. And while it was known that multifamily prices had skyrocketed since 2000, and that eviction filings in New York City have ranged between 175,000 and 190,000 per year in the last decade, our research draws a direct connection between speculation and evictions at the building level.

But the story told by the report has positive elements, too. We combined these data with information about affordable housing investments and found that properties with affordable subsidies were much better maintained than private housing that was not subsidized – in some cases, having up to 75 percent fewer violations, depending on the year. We also found that affordable housing investments took buildings out of the speculative market and protected them from the harm that it can cause. These findings drive our recommendations and conclusions.

In conclusion, it’s worth reflecting on the value of this research, given that it reinforces longstanding claims made by tenants, organizers, and their advocates.

Our report will not be news to a tenant who was evicted by a predatory landlord. But for those who might not listen to their voices, it’s one of the first empirical studies to rigorously demonstrate the direct connection between profit and harm at the building level, and to point to a better way – where nonprofit, tenant and community ownership can build a different form of neighborhood wealth.

David M. Greenberg, VP of Knowledge Management & Strategy

David M. Greenberg, VP of Knowledge Management & Strategy

David is the vice president of Knowledge Management and Strategy for LISC, where he evaluates its impact in 33 cities and rural areas, and supports the learning and evaluation needs of local offices and national programs. Before LISC he was a Senior Associate with MDRC, directed policy and advocacy for a coalition of 90 community housing organizations in New York City and organized with homeless men and women in the municipal shelter system. He holds a Ph.D. in urban and regional planning from MIT, and is a part-time faculty member at The New School’s Milano School of Urban Policy.

@dvm_greenberg