LISC’s Health Access Fund helps people living on low incomes, in rural and urban places, get to and from the destinations that play into their health and well being, from doctor's appointments to social service centers to the grocery store. Last year, with support from Uber, PayPal, and Walgreens, that amounted to 137,000 rides, helping upend a host of barriers to accessing healthcare and essential services.

Top photo: Members of Sisterweb, a nonprofit organization that supports Black women through pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period.

So much of what people do to take care of their health involves going someplace. A medical clinic. A community center. Even a grocery store. Sometimes the required journey is just too difficult and costly to manage. And, publicly-funded resources available in the community may feel or actually be out of reach due to scheduling or access limitations. More than 137,000 times in the past year, LISC’s Health Access Fund (HAF) has applied a solution to this recurring problem that’s proved flexible and effective: comfortable, cashless rides with Uber.

Uber offers a non-emergency medical transportation solution that is efficient and seamless. Couple that with personalized support and scheduling taken care of by the HAF organizations, and riders can focus on what matters most: their health.

The Health Access Fund is operated on the ground by local organizations close to the populations they serve, whose staff can offer no-cost rides to those in need, request those rides on the Uber Health platform, and track those rides to ensure a successful journey. With funding support from Uber, PayPal, and Walgreens, this transportation assistance is focused on individuals and families living on low incomes and rural residents—groups that confront a whole host of barriers to accessing healthcare and essential services, often resulting in poorer health outcomes.

Consider these real-life scenarios:

- In San Francisco, an expectant mother is stressed about getting to her care appointment at a major medical center. She calculates that taking public transit would add two hours to her outing, boosting babysitting costs for her other kids; but driving means scrambling to feed the meter if the appointment runs long (she’s been ticketed before) and she definitely can’t afford the hospital’s garage fees. SisterWeb, a nonprofit organization that supports Black women through pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period by pairing them with Black-identified doulas, arranges rides with Uber to and from the medical center. The woman has her transportation arranged for her and gets to and from her appointment in an easy, stress-free manner with no out-of-pocket or unexpected costs.

- In Clarkston, Georgia, a community outside Atlanta where over half of residents are immigrants and refugees, a family from Afghanistan shows up at the Ethne Health Clinic hoping to receive care. Staff of the faith-based clinic that serves patients regardless of insurance are accustomed to providing translation, including in Dari and Pashto, the major languages of Afghanistan. But without advance notice the appropriate translator is not on site and has no way of getting there. The clinic dispatches a ride with Uber to quickly fetch the interpreter, and a conversation begins about the family’s health concerns.

- For an elderly man in the Washington, D.C. area, round-trip rides with Uber arranged by the National Hispanic Council on Aging (NHCOA) make it possible to travel three times a week to a culturally welcoming, multilingual senior center where he can socialize, enjoy a meal, and exercise. The elder and his caregiver get to the senior center with Uber, making the trip less physically and financially taxing for both.

“What we’ve discovered is that transportation is a baseline social determinant of health, a kind of skeleton key,” says Erin Kelley, LISC director of health initiatives. “People are highly motivated to seek health and other essential supports for themselves and their families, and our local partner organizations are eager to serve. When these organizations are able to offer accessible, affordable, and flexible transportation to their patients and clients, they unlock opportunities to improve the health of those individuals and families.”

Tailoring transport to micro-local needs

To stand up these transportation solutions, LISC selected 27 local organizations across the country to receive grants under the HAF. Located in 22 cities across 17 states, these organizations include free and charitable clinics, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), hospital systems, affordable housing programs, and social service providers.

The HAF empowers grant partners to act as pragmatic problem solvers. Rides with Uber can be scheduled in advance or summoned for immediate transport. Riders can bring their children or helping companions, along with car seats and walkers. The rides are also available to transport health care workers to where they need to go. Just as important, they can and are being used to pursue not just medical care but any activity that promotes health—to get food, enroll in public benefits, or break out of social isolation, for example.

The NHCOA takes an “intergenerational approach” in its rides initiative for Hispanic seniors, says programs director Christine Perez. Paid and unpaid caregivers, including adult children and grandchildren, can take rides with Uber to support their elder’s health, picking up groceries or prescriptions, or to quickly close the distance separating them from the person they care for. NHCOA has booked more than one thousand rides with Uber.

Marna Armstead, co-founder and executive director of the SisterWeb doula network, is keenly focused on reducing stress for women of color during a crucial transition. Black people in the U.S. are at heightened risk for pregnancy complications, preterm birth, and maternal and infant mortality. And stress—“stress because the system has been racist, and they’re in the system, and they can’t get out of it”—is a key mediating factor, says Armstead. Many of the women whom SisterWeb doulas attend live in neighborhoods underserved by public transit—not to mention, climbing the famous hills of San Francisco to get to a bus stop when pregnant, in labor, or with a newborn in arms is not something people choose if they can avoid it. Offering rides through Uber has been a way for SisterWeb to treat birthing women “with dignity and respect,” Armstead says.

The rides have also helped the network’s doulas do their work. One had depended on a personal car that was nerve-rackingly unreliable after years of wear and tear. Another doula got a call late one evening that her client was at the hospital in labor. The doula summoned a ride with Uber, readied herself with haste, and was at her client’s side within the hour.

Demand for on-demand transportation

The HAF has evolved in response to a huge and underrecognized need. It began in spring 2021 when Uber, PayPal, and Walgreens invested $11 million in a LISC-managed fund to advance vaccination against Covid-19, then just ramping up. The Vaccine Access Fund facilitated more than 50,000 rides with Uber to vaccine centers and other health facilities for populations that faced the brunt of the pandemic’s health and economic crises yet lagged access to lifesaving inoculations.

Once on-the-ground organizations were fully trained in using the HIPAA-enabled Uber Health platform for booking rides and saw how they could integrate no-cost rides into their daily operations, demand exploded. This was the impetus for the HAF with its broader terms and objectives.

Sostento, a national nonprofit that supports a network of free and charitable clinics across the Midwest and Southeast (including Georgia’s Ethne), made the vaccine-access rides available to 15 clinics. While these clinics embraced the opportunity, dozens more joined a waitlist hoping to be included. When Sostento trained and onboarded 15 additional clinics to utilize no-cost rides with Uber through the HAF, one clinic in Miami reached out to every single patient to assess transportation barriers and saw an instant surge in the number of rides booked on behalf of their patients.

The clinics in Sostento’s network are staffed to varying extents by volunteer providers and treat severely underserved patients. The majority of rides arranged with Uber in the network have been for people with no insurance coverage and living on annual incomes of $20,000 or less. Short rides have spared people walking to clinics in last summer’s dangerous heat. Much longer rides costing as much as $90 have provided a way—the only way—for some rural residents to access care.

The rides have allowed clinic staff to forge stronger ties with patients and foster a critical sense of “psychological safety” in the trip from home to clinic, says Emily Ronning, Sostento director of partnerships. “They’re making sure patients understand that this is a trusted ride, and has a relationship with the clinic,” she says. “That’s a piece that feels specifically tailored to the audience.”

Incubating smart, supportive transportation

Indeed, the HAF has supported localized, organic innovation. While most of the grant partners use rides with Uber, four organizations in rural areas where drivers may be less available have designed their own transportation mini-systems. For example, Unity Care NW, an FQHC in Whatcom County, WA, is using HAF grant funds to reinvigorate a mobile dental clinic that visits public schools, Head Start programs, and child care centers across the county to provide dental screening and preventative fluoride treatments for children. A particular boon to residents of the mountainous eastern part of Whatcom County where many experience poverty, this outreach ends up connecting families to the clinic, where they can get affordable, whole-person care. Unity Care’s on-the-go dental clinic had been shut down by the Covid-19 pandemic; this school year, it is on track to treat a record number of children.

RUPCO, a partner based in New York’s Hudson Valley region, devised a simple system for carrying seniors to health care appointments from four rural affordable apartment complexes. It consists of a little Kia, a driver and social worker, Lori Gross.

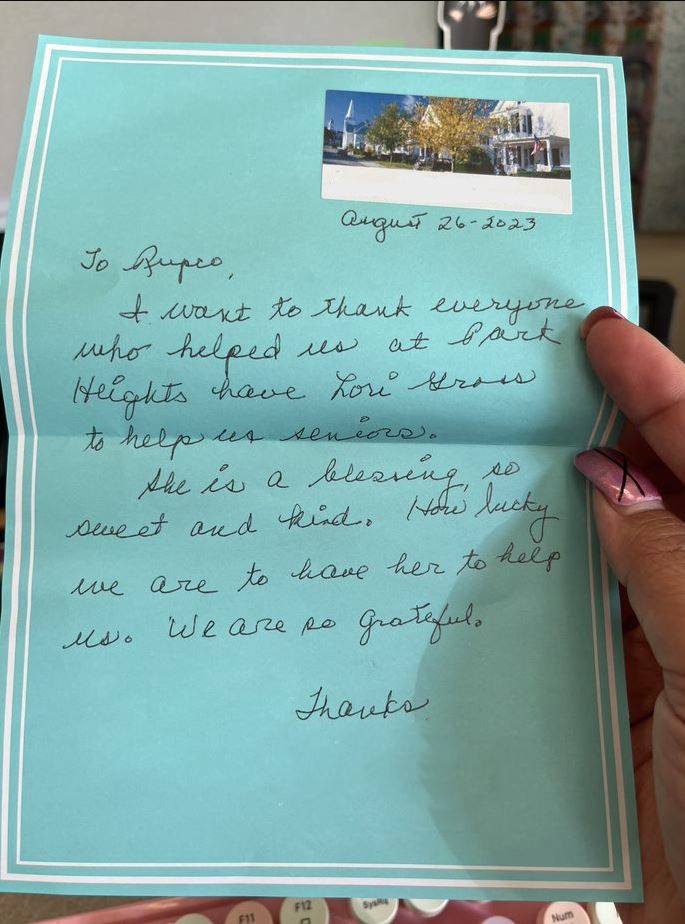

A thank-you letter from Josephine, 91, a retired school bus driver and rural resident, who was able to get to her medical appointments thanks to Health Access Fund rides arranged through LISC partner RUPCO.

Gross quickly realized that driving residents to get needed care is an intimate experience that draws a person into their lives. She began scheduling appointments for the elders, accompanying them into the doctor’s office and taking notes when asked, communicating with family members and medical providers, and more. Gross has found specialists to help a formerly homeless man who suffers from deteriorating vision and chronic pain; helped a resident get evaluated for untreated mental health issues; served as a caring presence to a woman who had been putting off going to the doctor after a frightening diagnosis; and assisted a resident acquire an electric wheelchair.

Josephine M., 91, is a retired school bus driver who has lived at a RUPCO senior community in Rosendale, NY, for more than 20 years. She has some trouble getting in and out of shops and climbing stairs but manages well at home. “I mostly stay here,” Josephine says. “We have dinners and potlucks and things like that, bingo. And I have a computer. I write letters. I have pen pals all over the world.” Like many of her neighbors, Josephine has found a friend in Gross, who’s taken her to Albany for skin cancer surgery, a hospital for an ultrasound, a foot doctor—and also introduced her to Bananagrams, a word game she’s now hooked on. “Have you met Lori?” Josephine asks, using Gross’s first name. “We’re all so grateful. She’s a wonderful person, so sweet and kind.”

Driving impact

LISC has engaged a third-party evaluator to study outcomes from the HAF in order to assess implementation challenges and to understand where the rides are having the greatest impact. But it’s easy to see how breaking down silos between the transportation, health care, and social-service sectors introduces certain efficiencies.

With Gross combining driving with sensitive case management, for example, “we have fewer calls to our property management team, to our property maintenance line,” says RUPCO director of program services Kelsey Vargas. In fact, at one RUPCO site, isolated seniors had often resorted to calling the town’s emergency services for routine trips to the doctor, racking up substantial costs. Under the HAF initiative, non-profit clinics have been able to fill unused slots in their schedules by reaching out to patients to offer same-day appointments and door-to-door, easy transportation. The HAF’s assisted transportation has supported the continued independence of riders like the senior in D.C., while reducing burdens on family caregivers, volunteers, and health care workers.

HAF grant partners are full of ideas about ways to expand and improve the service and are concerned about what happens when the HAF’s private investments run out. “’Don’t take the rides away!” is how Ronning characterizes the attitude of Sostento network clinics. SisterWeb’s Armstead says the program has given the organization a chance to see what it’s like “to fully hold our community.” Along with this experience came actionable information for policymakers and funders: using rides with Uber to support the health of Black and Brown mothers is “doable,” Armstead says, “not super expensive,” and “really a blessing to our clients and our staff.”