As our country celebrates LGBTQ pride, we're focusing on some of the challenges for LGBTQ people living in rural America. Community developers are in a key position to support LGBTQ rural residents as part of our work helping build flourishing and inclusive communities.

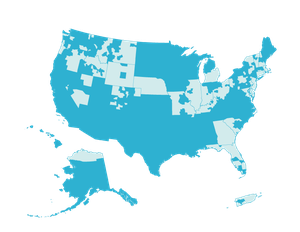

Top image courtesy of the Movement Advancement Project.

This month, in cities and towns all throughout the country, rainbow insignia and proudly flying rainbow flags festoon everything from civic buildings to store fronts to ride share apps. Parades, exhibits and countless other events are commemorating LGBTQ identity and the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising that set the gay civil rights movement in motion.

Even in 2019, though, public celebrations of LGBTQ pride aren’t the norm in every part of the country. Witness a recent Facebook post by the owner of a 1991 Chevy pickup in Oklahoma emblazoned with a pride flag and a slogan that reads: “Not all country boys are bigots. Happy Pride Month”. The post went viral—and its author, a straight man, received scores of messages from rural residents telling him of discrimination they’d faced, and of how grateful they were for the show of support.

In fact, though rural America is home to a robust population of LGBT people—as many as 3.8 million or some 20 percent of the country’s total LGBT population—discrimination and isolation are still particularly severe challenges for queer residents in America’s rural areas. Those conditions are interwoven with exclusion from employment, housing and other opportunities, and with marked health disparities.

Such challenges, and the role community developers can play in helping upend them, were the subject of a panel discussion at LISC’s annual Rural Seminar earlier this month called “Fighting Isolation and Striving for Inclusion Among LGBTQ Populations in Rural America.” Speakers described the current hurdles to economic and social wellbeing, but also offered dozens of recommendations for supporting LGBTQ people in rural communities. “Even in the community development field, where we work to promote inclusion and equity, LGBTQ issues are not at the fore,” said Michael Levine, former LISC chief counsel, who moderated the panel. “CDCs can play a huge role in leading by example.”

While popular culture suggests that all LGBTQ lives are urban lives, not only are LGBTQ people part of the fabric of rural America, they choose to live there for the same reasons as anyone else. That’s one of the findings of a recent report by the Movement Advancement Project (MAP) titled “Where We Call Home: LGBT People in Rural America.” Logan Casey, a MAP researcher who authored the report and spoke on the panel, pointed to family and community ties, connection to nature, and love for a slower, more organic pace of life as the principal draws LGBTQ people describe about living in rural America.

LGBTQ residents of rural areas face many of the same challenges as their neighbors (high rates of poverty; a scarcity of economic and educational opportunities; few health care, housing and culture resources), yet they experience different consequences. And living in rural communities can amplify the sense of isolation and rejection. “Majority rural states are less likely to pass laws that offer protections for LGBT people,” Casey said, “and more likely to have discriminatory laws, such as allowing religious organizations to opt out of providing services for LGBT people if they feel doing so clashes with their beliefs.” In May, for example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a rule expanding health care workers’ ability to refuse services on religious grounds, and the measure has been embraced by many rural states. "People shouldn't have to choose between the community they come from and getting their basic needs met, with dignity," Casey added.

Health disparities, in fact, are a critical issue for rural LGBTQ residents. According to panelist Miria Kano, a medical anthropologist with the University of New Mexico’s Comprehensive Cancer Center in Albuquerque, LGBTQ people in rural areas suffer disproportionately from anxiety, depression and other behavioral health problems. LGBTQ youth and seniors, especially, have high rates of drug use, homelessness and suicide. They’re more likely to encounter rejection or ignorance when seeking support or medical assistance. “Many have lost hope; they don’t feel safe,” said Kano, who works in dozens of rural counties in New Mexico and other parts of the country. “They may be facing discrimination in the household as well as in the community at large.”

Another panelist, Roberto Jiménez, who directs Mutual Housing of California serving the Sacramento Valley, also noted the special struggles of LGBTQ seniors and youth. “I meet seniors who are going back into the closet because they’re afraid they can’t get housing otherwise. They’re experiencing violence, threats of homelessness. The need on each end of the age spectrum is huge.”

Members of the audience, too, cited examples of anti-LGBTQ discrimination and violence percolating to the surface in their communities, especially in the years since the last presidential campaign. One CDC partner recounted how a car belonging to a gay couple in his rural town recently was turned upside down in the driveway, and their house spray-painted with epithets. He and his colleagues, he said, were feeling helpless against a rising tide of hate crimes and overt bigotry.

This, the panelists agreed, is where CDCs and other community organizations can have a crucial galvanizing effect in their communities. “Sometimes just being present is the most important thing you can do,” said Kano. Or as Roberto Jiménez put it, “the only way to effectively address this is to build community.”

The MAP report devotes 11 full pages to recommendations, including for community organizations working in rural areas—dozens of ways to strengthen the social, political and economic climate for LGBTQ people, to improve local policy and support structures, and to create safe spaces.

A good first step, the panelists agreed, is for community leaders and other residents to lobby their local elected officials to enact antidiscrimination measures. Community-based organizations can themselves adopt nondiscrimination policies, conduct cultural inclusivity trainings and include questions about orientation and gender identity in community needs assessments, among many other actions. While addressing the needs of people in rural communities generally, organizations can also take into account LGBTQ experiences specifically—creating lasting, positive change. And this runs the gamut from overarching policy change to small gestures of solidarity.

“Put a tiny little rainbow sticker on the window of your organization’s office,” said Kano. “Even if it’s in the back window, someone is going to walk through and see it. That one thing will reify their existence and let them know they’re acknowledged.”