Pain and Progress Through a Rural Lens: Community Violence Intervention Beyond Urban America

Community Violence Intervention (CVI), an approach to quelling crime and supporting people who may be victims of, or likely to commit, violent crime (or both), emerged in America's urban neighborhoods. It is now practiced across rural America, too, sometimes in forms that vary distinctly from city-based CVI. LISC's Safety + Justice team, in tandem with Rural LISC, invest in capacity building for these groups working round the clock to make their communities safer, and to save lives.

Leon Burden was sitting in federal prison, nearing the end of a 15-year term, when he felt God calling him to return to the place where he was born and raised, rural Robeson County, NC, and devote himself to healing some of the harms he’d both caused and suffered as a young gang leader. That was nearly 20 years ago. In the youth Burden works with every day, he sees himself. He’s what’s known in the field of community violence intervention (CVI) as a credible messenger.

Paul Smokowski is a researcher and program director in youth-violence prevention. In 2010 he began a university-based, federally funded research intervention focused on Robeson County. He’d drive back and forth from his Chapel Hill campus, two hours one way. Smokowski came to believe that resources committed to reducing violence in Robeson County needed to stay in Robeson County, and to do the work most effectively, so did he. In 2014 he helped found the local nonprofit he leads today, the North Carolina Youth Violence Prevention Center (NC-YVPC). And he made Robeson County his home.

They’re just two individuals. But in a sprawling, underserved, yet close-knit rural county like Robeson, the commitment of a few can represent pivotal capacity—in this case helping to assemble the local expertise, partnerships, and resources necessary to stand up CVI, a relationship-building approach to quelling violence developed on the streets of big cities like Chicago, Boston, and Los Angeles.

The reality of rural violent crime

Smokowski and Burden were among the rural practitioners who took part in a panel discussion on what CVI looks like outside urban centers at a recent conference in Chicago sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), together with LISC. The session, organized by LISC Safety & Justice team’s John Connelly, was part of a gathering of mostly urban grantees in the DOJ’s Community-Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative (CVIPI). With its dedicated rural program, LISC is committed to investing equitably in rural America. And as technical-assistance providers, says Connelly, the LISC Safety & Justice team is working to bring attention to the needs of rural jurisdictions and help them develop models for CVI that work in rural contexts.

One thing the session accomplished was to pierce the myth that gangs and gun violence are exclusively urban phenomena. Ainka Jackson, founding executive director of Alabama’s Selma Center for Nonviolence, Truth, and Reconciliation, cited a recent article in The Trace headlined “You’re More Likely to Be Shot in Selma Than in Chicago.” “That’s the reality,” Jackson said. With its team of outreach workers and partners, her organization has been able to help prevent gun violence and behavioral issues from rising among its clients, she said. But the group also has to worry about struggles like hunger and mass displacement from a 2023 tornado. “When you talk to foundations, they’re like, ‘Y’all are doing a lot,’” she said. “Yes, because we have to.”

Smokowski shared a chart showing that Lumberton, NC—Robeson County’s largest town—also has one of the highest violent crime rates in the U.S., a fact that gets buried when the focus is on raw numbers. Several of the county’s smaller towns have rates five to ten times the national average. “That’s why I’m passionate about this narrative,” Smokowski said. “They don’t get the resources.”

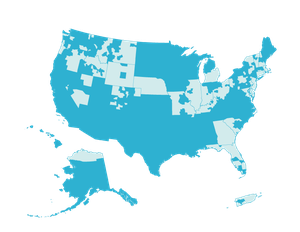

In fact, according to Rural LISC senior program officer Julianne Dunn, although roughly 20 percent of Americans live in rural places, in a typical year they receive well less than 10 percent of philanthropic and federal grants. That’s partly due to jurisdictions’ lack of capacity to compete for and manage grants with complex requirements. It also reflects funders’ own expertise and focus. “When people hear ‘rural,’” said Jackson, “they literally tune out.”

Building capacity for change

Robeson is among North Carolina’s most racially diverse counties, its population of 117,000 a mix of Lumbee Indian, Black, white, and Latine residents. It is also one of the poorest, which affects the availability of services from health care to public safety. “Lumberton is the seventh most dangerous town in the country,” said Smokowski. “How many police cruisers do you think they have on a Saturday night? Three. Two of them are at the bowling alley. The third one is in the Walmart parking lot.”

NC-YVPC is a small shop, too, with about 15 staffers. But it does have the ability to win grants and braid funding from agencies like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and DOJ. That’s important for its partners, and to support an anti-violence program that includes primary prevention (parent education and youth mental health first aid, for example), targeted interventions like violence interrupters, and a teen diversion court as well as trauma-focused therapy for crime victims and youthful offenders. The organization is currently working with a $2 million CVIPI grant to extend these initiatives from Lumberton to the rest of the county.

LISC’s approach to rural needs is often to support basic organizational capacity building and help foster coalitions that magnify power. In Robeson County this has meant advocating for the approval of DOJ grants to four municipal police departments within the county—in the small towns of Fairmont, Pembroke, Red Springs, and Rowland—to allow them to closely partner with the NV-YVPC. All four grants under DOJ’s Rural Violent Crime Reduction Initiative (RVCRI) were approved last year. “It’s unusual to see resources like this concentrated in one county,” says LISC vice president for Safety & Justice Mona Mangat. “But we think it’s incredibly important. The capacity to collaborate is key to developing a program in Robeson County that might be a model for other rural places.”

The grants help cover overtime for officers to take on special assignments, including community outreach and liaising with NC-YVPC to implement victims services and CVI. These under-resourced small PDs, facing high rates of violent crime, have had little leeway to tackle such proactive measures. “It’s like a treadmill that’s on high,” says Smokowski, “and it’s hard to keep up.”

Connelly works with the four police agencies as their technical-assistance provider. In one case, he helped adjust the grant budget to allow for updated computer equipment so that department personnel can fully participate in Zoom calls. Perhaps most tellingly, though Connelly invited the chiefs or their designees to attend the April 2024 CVIPI conference in Chicago, none had the staffing capacity to leave their posts for three days.

Rural methods for rural places

In rural areas, as Jackson suggested, people often wear many hats. A town mayor may also run a local business and volunteer in the schools. CVI is no different. Big-city violence interrupters typically draw a bright line between themselves and law enforcement, to maintain trust with those at highest risk of being involved in violence. In Robeson County, that strict separation is unrealistic, for two reasons. Divisions of labor aren’t as workable in a rural place where there are only so many personnel to address the problem of violence. And people tend to know one another anyway.

NC-YVPC’s team of violence interrupters includes Burden (he also helms his own nonprofit, Colors of Life, and serves on the NC-YVPC board), a beloved longtime high school football coach, and two women police officers, one active and one retired. Burden has walked with police on community beats, chatting up residents and business owners. (If they seem reluctant to talk, he’ll circle back by himself.) He’s been involved in helping police search for missing persons and identify weapons in schools. He’s had scared local youth come to him saying they messed up, advised them on finding a lawyer, and supported them as they faced legal consequences.

Even as it makes anonymity harder to come by, the social connectedness of Robeson County is a form of capacity that’s distinctively rural. Years ago, when Smokowski wanted to get acquainted with the county schools superintendent, Burden simply pointed him to a local chicken place where the official ate lunch on Wednesdays. That began a productive collaboration.

Another obvious difference in rural CVI is the geography it has to cover. At the Chicago conference Burden heard urban practitioners talk about creating intensive presence on certain “blocks.” Well, Robeson County is 950 square miles—about four times the size of Chicago—dotted with small towns. “I drive,” says Burden, “and then I get out. I walk around. I might go to football or basketball games. I sit and talk with the youth. ‘Why y’all walking around in cliques?’ My thing is, ‘Put your gun down and let’s talk.’” The violence interrupters get around the county on a regular basis, but just closing the distances adds person-hours to a job that’s already time-intensive.

Pain and progress through a rural lens

Eruptions of violence can also be felt differently in rural places, touching interconnected social networks and affecting whole communities. “The impact of these crises can be very high,” says Smokowski, “because people know each other and you’re more likely be involved, directly or indirectly.” In Chicago he and Burden spoke of a gunfight that took place last September during a football game at Lumberton Senior High. “No one was injured,” the local Robesonian reported, “but the shooting rattled the players and the 1,000 fans there to see the Lumberton Pirates take on the cross-county Red Springs Devils. For many families and students, it was another instance of celebration tainted by gun violence.”

The flip side: positive developments, even seemingly small ones, can also have ripple effects that wash throughout a rural community. Policymakers and funders often measure impact through an urban lens, looking for economies of scale and high numbers of people served, observes Rural LISC’s Dunn. In rural places, that’s not what progress looks like.

For years, Burden has been doing anything he can to connect Robeson County youth with paying work, putting out feelers and posting openings. “Some kid might say, ‘I want to be a barber,’” he says. “I’ll buy some clippers and give them to him.” Now the folks at NC-YVPC are talking about adding a critical workforce development pillar to their program. Meanwhile, the small-town police agencies are actively engaging with the nonprofit to support public safety in new ways. “We are very collaborative,” says Smokowski, “but you also have to have a vision for it: what’s the next thing that we can start to build?”