In honor of Hispanic/Latinx Heritage Month, we spoke with Rural LISC's Nadia Villagrán, to learn about her experience growing up in a mutual self-help community, and how it shaped her family's lives, her own world view and her career as a community developer and a Latina leader in rural California.

Nadia Villagrán has worked with Rural LISC for five years, currently as program director for Fund Development and Strategic Partnerships. She is also a leader of Comunidades, LISC’s Hispanic/Latina/o/x affinity group. Before coming to LISC, she spent nearly 14 years working with the Coachella Valley Housing Coalition, a longtime LISC partner that has helped build more than 3,000 USDA-supported mutual self-help houses.

Nadia, in fact, came to that work with deep personal experience in self-help housing—she grew up in a home her parents, both immigrants from Mexico, built with their neighbors in the early 1980s through the USDA’s Mutual Self-Help Housing program. That upbringing gave her a unique vantage on her chosen career: not only can she speak at ribbon-cuttings in both Spanish and English, she has advocated for USDA funding and policy from a resident's perspective, and encouraged tired families mid-build. And for the record, she knows how to use a circular saw and pour concrete.

In honor of Hispanic/Latinx Heritage Month, we caught up with Nadia to hear about her experience coming of age in a house and a community her family erected from the ground up, and how it shaped their lives, her own world view and her career as a community developer and a Latina leader in rural California.

Photo at top: (from left) Nydia, Lorena, María, Nadia and Nubia Villagrán, circa 1987. All images courtesy Nadia Villagrán.

Let's begin by talking about your family’s history—where did your parents grow up and how did they decide to come to the United States?

My parents are Luís and María Villagrán, and my dad always introduces himself “Luis Hector Villagrán, para servirle”—which means “at your service”—because he’s a really proper, proud Mexican. He was raised in a little mining town called Cusihuriachi in the Chihuahua sierra. It was a kind of Tombstone town—it had a huge boom for part of the 20th century when my family was living there. During its heyday, my grandmother owned the town restaurant in the local hotel, and my grandfather was the postman and the local carpenter.

My father was the youngest son of nine children and was left in charge of the home when everyone moved out. When the silver mines closed and the town died, he sold everything and moved with the family to Juarez, on the border with El Paso.

My mother also grew up in the Chihuahua sierra, in a small farming village known as Los Ranchos de Santiago, where her family worked and owned farm land where they grew fruits and vegetables. But they also moved to Juarez when a big drought destroyed their business. She and my father met at a dance in Juarez and as the story goes, when my father brought his mother and uncle to meet my mother’s family, my grandmothers burst into tears when they saw each other—they had known each other as children!

My parents married and had four girls—I have two older sisters, and when my twin sister and I were about to be born, my parents decided they should move the family to the United States.

What was that transition like for your family?

We first lived in Corpus Christi, where my father got a job working for the city maintenance department. Our first year in Corpus Christi, there was a huge hurricane, and he was busy boarding up the city buildings and didn’t get home to protect our house until the storm was well underway. My mother took that as a sign that we did not belong in the United States, so my parents picked up and moved us back to Mexico. Then, right when my twin sister and I were turning five and about to start school, we moved to Tucson, to a neighborhood that was considered so tough—it had high rates of crime and drug use—that there were literally signs saying “Enter this area at your own risk.”

My mom was always worried about us being exposed to things that we shouldn't be exposed to. My parents only spoke Spanish for the most part and there was a sense of fear and insecurity when we lived in Tucson that was palpable, that I could sense as a kid.

How did your parents find out about self-help housing?

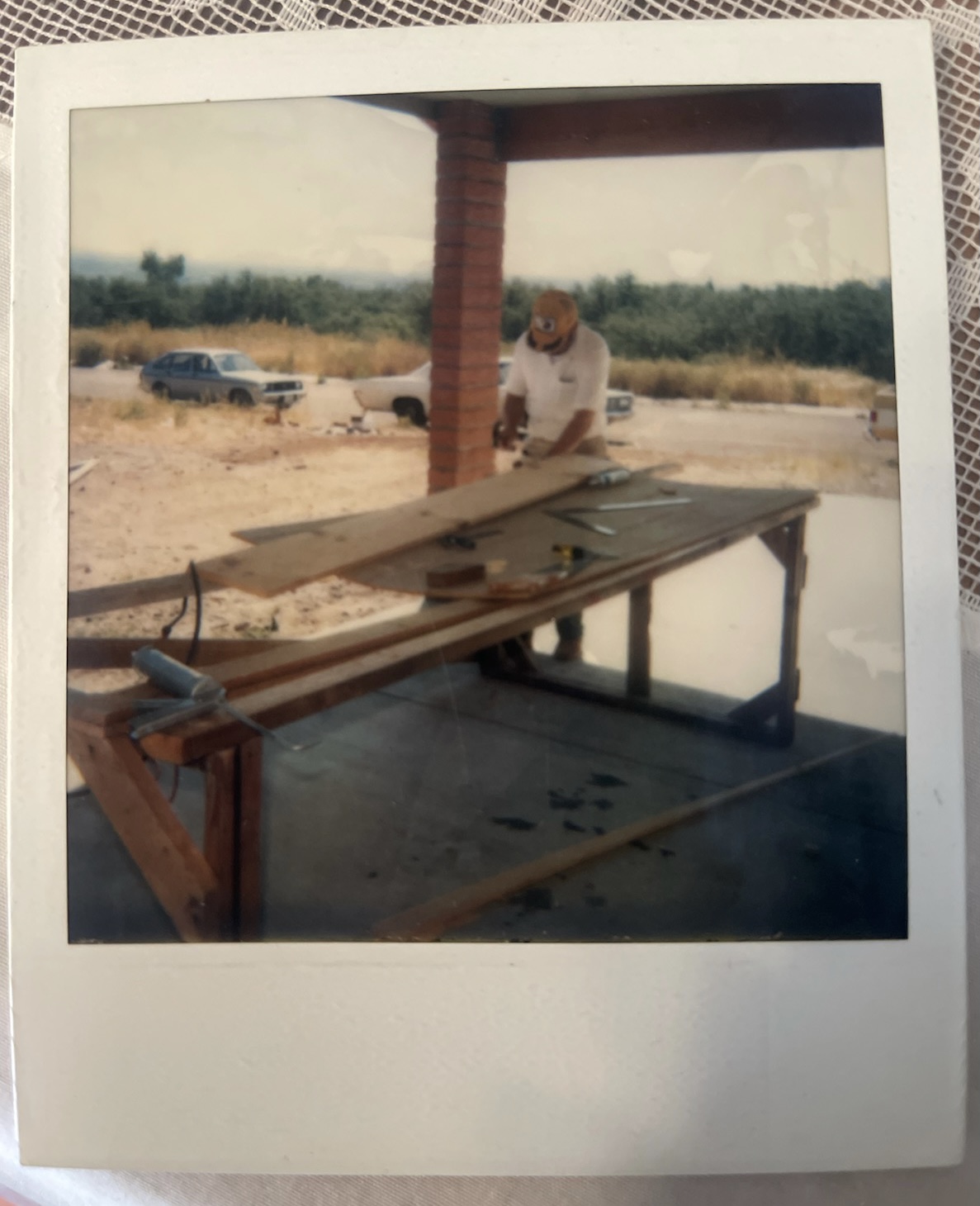

There was a nonprofit in our part of Tucson where my mom was taking English and citizenship classes, and that’s where she learned about this housing opportunity and the fact that families could build their own homes. My dad, being a carpenter—he learned carpentry from his dad—was really committed to the idea of getting assistance if it meant that he would provide his skills towards that assistance. Which is really the key to the program: that you invest your sweat equity and then you get assistance from the government to secure this loan.

And so sure enough, my parents signed up for the program. I remember going to the building where my parents had to do pre-ownership classes and a lot of paperwork, and my sisters and I would do our homework in the waiting room.

And then they started building the house. It was in a little town, about a 45-minute drive south of Tucson, on the way to the Nogales, Mexico border, called Amado. Amado means “loved” in Spanish, which my dad thought was a good sign because his grandfather's name was Amado Luis Villagran.

What was the building process like for you, as a child?

It felt like it took forever. But one of my best memories is of watching my parents on the roof of the house, installing shingles. They were working under a tarp because it was raining and I remember thinking that my mom and dad could do anything—not just my dad, but my mom, too.

Luís Villagrán, Nadia’s father, working on a home in Amado, AZ.

They worked with eight other families to build the first houses in the neighborhood, and because my dad was a skilled carpenter, he installed all the kitchen cabinets and every door for the whole group, and he was very proud of that.

Watching my parents go through the process of building, from the ground up, this stable environment for us really meant something to my sisters and me.

Do you remember what if felt like to move into the house?

We moved in on my sister’s and my seventh birthday. My parents said it was a gift for us, and we got to pick our own room, which was great for a seven-year-old. We were still sharing, but it was a much bigger place than the two-bedroom apartment we had before. In Tucson, we had bikes, but we weren’t allowed to go out on the sidewalk, we could only scoot around in the little yard. In Amado, we could bike anywhere. For the first time, my mother didn’t mind letting us out of her line of sight.

My sisters and I knew that we were finally in a place where my parents didn't feel they needed to protect us from going outside or from the neighbors. They knew everybody, everybody knew them. The whole community spoke Spanish so there wasn't that concern about misunderstanding people's motives. When you're a kid, that's all that matters: if your parents feel comfortable, then you feel comfortable. And we could feel that.

The values of family, community and contributing to the commonweal are not unique to Mexican and other Hispanic/Latino/a/x cultures, but they are strongly held, and those are clearly ideals your parents passed along to you. Can you talk about how the self-help experience meshed with those values?

I think there's a grace that comes with the program—you're asking your neighbors, who you just met, to give you their blood, sweat, and tears to build your house. And in exchange, you'll help them build theirs. There's a mutual respect, a mutual understanding of the immigrant experience and that focus of doing something that's going to improve your family and your community. I think that's why the program works so well, and why it works really well for Hispanic or Spanish-speaking families—because that attitude of helping oneself by helping others is ingrained in the culture.

For me, it's like a rural thing too. I don't want to dismiss the urban reality, but there's something to be said for a community that's really small, where people look out for each other and help each other in any way, down to primal needs like food and shelter and water.

How do you think those early experiences in your community shaped your view of the world?

In college, one of the jobs I had was working as a newspaper reporter, and because the editors knew I grew up in a self-help home, they started assigning me housing stories. I could see how my immigrant life was not the same as other people's, and that's when I started to realize that the housing program and this community that we created made a huge difference. I was talking to families who had very similar backgrounds as mine, but they didn't have a stable home or a secure, welcoming environment. And that can create trauma that’s layered into your childhood. It changes who you are and how you deal with people.

Nadia Villagrán at the ribbon cutting of a LISC-supported baseball field in Yauco, Puerto Rico.

I could see how lucky we were as a family, versus, say, another Mexican immigrant family with four girls, trying to get by. I think about how hard our life would have been if we hadn't been in our mutual self-help home when my dad hurt his back and was in the hospital and couldn’t work for a long time. My mom had to go to work as a housekeeper and didn’t earn the same income as my dad had. What kinds of choices would we have had to make? Would my sister, at 13, have dropped out of school to help pay bills or to keep a roof over our heads? You don't realize how important your home is until you see the unfortunate choices that other people have to make when they’re in a financial crisis.

A recent LISC research report, From the Ground Up, documents the ways self-help and other affordable housing in parts of rural California have contributed to the development of a middle class and greater political participation in those communities. Did you experience that kind of civic engagement in your family's life?

Definitely. I would say my mom was already a fierce, empowered woman when we moved to the United States. She knew we would have more options as women in the U.S. and she was always looking for ways to make our lives better. She pushed to get citizenship for herself and my dad before my older sisters, who were born in Mexico, turned 18. She knew that would make it easier for them to become naturalized citizens as well.

My mom knew how important voting was because, as she said, the people who were making the decisions about our community's children's education were doing it without considering the realities and needs of Spanish-speaking families and other immigrants in Arizona. This was during the phase when the state government wanted schools to be "English only." My parents recognized that they had a community leadership role in this process, that people were looking to them to be the brave voice, to challenge things, in those moments. And they were willing to do that. And they really impressed on us how important it was to do whatever we could to make the world better for other people.

At what point did you decide that you wanted to help other families build communities like the one you grew up in?

When I graduated from college, I moved to Palm Springs to take a newspaper reporter job. By then, I knew I wanted to be a social services/community development/nonprofit writer—I was going to find out who was doing what to help people. So in Palm Springs, I started doing stories on the Coachella Valley Housing Coalition, the nonprofit here that has the largest mutual self-help grant in the country. They build about a hundred units a year and they’ve built more than 3,000 homes at this point.

I loved doing stories on them and I used to talk to their director—we'd go get coffee and he’d tell me about what was going on, and by the third or fourth time, he said, “enough writing about it. You need to help us do it.” So I got a job as the grant-writer for the Coalition and I never looked back. The whole idea of helping make a community strong with my skillset of writing things down and being extremely pushy was perfect!

You had unique insights to bring to that work.

Well, at the Coalition, we were always pushing the envelope with what the USDA allowed and what they were willing to fund—pushing them to reconsider their idea of what affordable housing or farmworker housing should look like. The home my parents built in the early ‘80s was a 1100-square-foot house, with three bedrooms, one and a half baths and a one-car carport. When I started in this work, the biggest we could go was 1,200 square feet. But by the time I was running the mutual self-help program at Coachella Valley Housing Coalition, we were building 1,800-, 1,900-, nearly 2,000-square-foot houses, based on size of family, with full bathrooms and full garages.

We even had to fight for fireplaces. For communities where it's cold, having a fireplace is another great way to save on heating. But the USDA did not think it was appropriate for houses to have the luxury of a fireplace. Being a product of the program, but also a part of the program, I could explain in first person why these things mattered, and challenge people's misconceptions about what poor people deserve and who poor people are.

During much of the 20th-century, people of color in the U.S., including immigrants, were intentionally excluded from homeownership and the asset- and generational wealth-building that can come from that. Self-help housing really was and is an antidote to that exclusion. Have you been able to see that positive impact, both in the communities where you’ve worked and in Amado, where you grew up?

I absolutely have. In Amado, our self-help homes were built on the top of a little hill, and at the bottom of the hill there was a mobile home park. People did their best to keep it clean and pretty, but it was overcrowded, very, very low-income housing.

The people who lived at the bottom of the hill would go up the hill to ask for daily labor work. If someone came to the house and said “can I please iron your clothes for money,” my mom would always say “yes.” Or someone would ask, “can I please mow the lawn for assistance?” or “can I please take your trash, your recycling?”

All these things that my parents probably did for other people in the course of their lives, and that my mom was still doing as a housekeeper, they were now employing people who lived at the bottom of the hill to do. My parents explained that even though we were also very low income, we had to recognize our good fortune and share it with others who were simply searching for honest work in order to provide for their families. We were only better off by extremely minor degrees, but it made all the difference. The only reason this family on the top of the hill was better off is because of this program, and this very unique self-help mortgage that worked with you, through the good and the bad.

I definitely saw the change in the community as a result of the program, and the community still stands. It's still a vital place for affordable housing 30 years later. But the roots of this program grow so far beyond housing.