Nadia Villagrán, Rural LISC’s new leader, brings a lifetime of rural experience, and a career’s worth of know-how in rural development, to the job (not to mention eight years in various roles on the team she now leads). In the following Q+A, she shares her vision for the work, her insights into the special challenges for rural, and the reasons her childhood in the Arizona countryside still guide her approach to making impact.

Image above: Villagrán at the opening of a baseball field in Loiza, Puerto Rico.

Nadia Villagrán, who was recently named the head of Rural LISC, has spent the better part of two decades honing the expertise required to be a national leader in rural community development. But some of the insights that shape her leadership today percolated in early childhood.

Villagrán grew up in the tiny rural town of Amado, AZ, some 40 miles south of Tucson, in a three-bedroom home her parents helped to construct. In fact, working with eight other families, Luís and María Villagrán, immigrants from Mexico, built themselves a small, close-knit community in Amado, supported by technical assistance and affordable mortgages provided through USDA’s Mutual Self-Help Housing program.

Villagrán remembers watching her mom and dad install shingles in the pouring rain, and thinking they were like superheroes. She recalls the excitement of moving into the new brick house on her seventh birthday, a gift that literally kept on giving: the safety and permanence of that home made so many other things possible for the Villagrán family

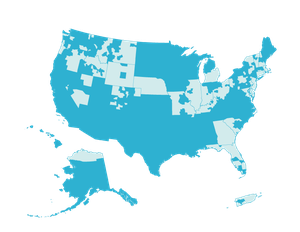

Before coming to LISC in 2017, Villagrán spent 13 years paying those experiences forward. She worked for Coachella Valley Housing Coalition, a Southern California nonprofit that has helped thousands of low-income families build and own their own homes. At Rural LISC, Villagrán has managed a variety of initiatives and programs including fund development, strategic partnerships, and communications. She was named Rural LISC director in March. Here, she answers our questions about what’s happening in rural community development and her aspirations for the Rural LISC network covering more than 2,400 U.S. counties.

Let’s start with the big picture: what does “rural” mean to you?

It’s funny because I always say that I'm a rural girl. When I’m introduced in small groups, I say that. It’s clear that “rural” is a geography, but I’ve heard it said that it's also a culture. It's what defines my philosophy on life a little bit. I grew up in a rural community where everybody helped each other. Everybody was coming at life’s struggles from the same direction, trying to help their community and their family and their children improve. They recognized that because there weren't a lot of people, and it was a very large geography—beautiful and natural, but a large geography—that people had to help each other. They had to talk to each other. They had to step in when there was need.

That's what rural means to me. It's always been a driving force in how I see my contribution to the world and, very importantly, to rural communities—being willing to step in and provide my particular skillset to that work.

What would you say are the most pressing needs of rural communities? Have these needs changed?

I feel like what rural communities need today has less to do with simple things then it used to. For a long time, we talked a lot about transportation being a challenge for rural communities. We talked a lot about access to capital being a challenge. I think nowadays, because the internet and remote work have made the transportation challenge a little more manageable, the struggle is technology and broadband and connectivity and the skills associated with this tech world that we're exploding into.

We're in a moment where AI development and financial tech resources are ballooning, and some communities are so technologically connected that they're leaps and bounds ahead of the small towns and rural communities that we work in. We at Rural LISC are committed to helping them get to an even footing.

On the positive side, more and more people are recognizing the entrepreneurial spirit in rural communities—people who have these really interesting ideas, these crafts that they can do, this cultural or community awareness that they've been thinking about making into a small business. Because of globalization, remote work, and technology, there are more and more ways to maximize those ideas and abilities into a marketable business.

What are your top three priorities for the next two to three years at Rural LISC?

There are so many things that we want to do. Number one, and it’s far-reaching, is ensuring that rural communities and small cities have an equitable bite at this large federal apple, all of these incredible public-dollar programs—including the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program (BEAD), the infrastructure funding, the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) funding. Our goal on the rural team is to help communities get themselves ready for these dollars, so they can successfully apply, successfully consider what they can use the funds for, and then implement that use appropriately.

Second is incorporating green, energy-efficient, resilient building into the work that's happening with those dollars in rural places, not just in housing, but also in the infrastructure. How can broadband be developed with an energy-efficient and resilient mindset? Are we doing this in the most thoughtful and forward-thinking way? When you have a large infusion of dollars, that's when you get the chance to ask these questions. We need to be helping communities not be afraid of the cost that might be associated with a forward-thinking answer, because there's an opportunity now to use these federal resources for that.

And third, housing. For us at Rural LISC housing is always going to be a top priority. We know through years of practice that “house” can be the catalyst for everything else. In my personal experience, once your housing is stable, then you can do so many other things. I think that rings true in most rural communities. If you have your residents living comfortably in a safe and clean and healthy environment, they can start making big decisions about childcare and upskilling their own skillsets to look for better jobs and all of the above.

Can you give an example of how an influx of capital right now can be used in an effective and, as you suggest, ambitious way in rural communities?

I’ve been working in community development in California for many years, and California has been mandating very far-reaching environmentally conscious development models for years. California-based affordable housing developers, for example, have incorporated net-zero energy, water reclamation, and energy-efficient building design and product models into their housing.

I would say, let’s not be afraid to use those models in rural parts of Kentucky and Louisiana and Maine and Mississippi. The beauty of it is these small cities and communities don't have to try things out and learn that they don't work, which has happened in California. We just get to cherry-pick the successful stuff and put it into practice in rural places.

You talked about the huge influx of public dollars right now. Can you talk a little bit about private funders and what that landscape looks like right now?

Philanthropy is committed to investing in rural communities. We've certainly seen that in the last, I would say, seven years. What's been difficult is with this influx of public money—billions of dollars—there's a very clear expectation of a match. It's taken philanthropic organizations a little while to embrace the fact that they're inadvertently being called upon to solve this gap. There's so much potential risk. The funds might get pulled back by the public entity if the group didn't do the work right, for example. It's been a labor of love of helping philanthropy to recognize their role in this new funding stream. That work is beginning to see results.

You’ve been working in this space for years. Are the challenges to doing affordable housing in rural places changing?

Rising costs are at the top of the list: the cost of rural insurance, the cost of acquiring land, the cost of the money needed to build affordable housing. All of the above is really very challenging.

There's a capacity issue as well. There are incredible, experienced nonprofits across the country. Unfortunately, they don't serve all the rural places where affordable housing is needed. But there are important nonprofits open to doing this work that need a little capacity building and support to help make affordable housing possible in their communities.

Additionally, nonprofits not only need to know what they are doing, but they also need really strong financials. You may know how to do it. You may know where in your community an affordable housing development would be welcome and successful. But if you don't have the financial capacity to apply for the funding to acquire the land, to apply for the public dollars and the tax credits, your skillset is lost. So, our job is to reinforce nonprofits, support organizational development, teach technical skills. Then, of course, our role as a CDFI is being willing to take risks with those groups, because nobody else will.

If there were one thing you could make sure people understand about rural America, what would it be?

Rural America is more diverse, innovative, and entrepreneurial than people give us credit for. People often talk about rural places taking lessons from urban experiences, but there are a lot of lessons to be learned about success and advancement and entrepreneurial creativity in rural places that can be mirrored and scaled in small and large cities. I think that the community development industry can learn a lot from what is working in rural places.